After yesterday’s rain, today, sunshine greets our return to the National Museum, where Stephanie Burge and education department head Eleri Evans greet us with a smile. Steph, as discussed, awaits us with a VR explorer. We are excited and, small-screened device in hand, head off in the direction of the exhibitions, eager to discover what a digital apparatus such as this can contribute to an exhibition that already seems so appealing. Our first opportunity arrives with a room in the first-floor fine arts gallery featuring the works of French impressionists. There, the device offers up a display of Monet’s Water Lilies, transforming the room into Monet’s garden at Giverny with its familiar bridge, upon it the Master himself gazing down as fluttering butterflies float about the previously empty room. Following a green pathway projected onto the floor, we arrive to Renoir’s woman in blue, where a virtual lady in period dress tells us about the painting and how it was created. Soon after, we learn about the works of Cézanne in a similarly digital way.

We notice that, in the meantime, an older woman has entered the room pushing a bright red tea trolley. She quietly unloads the cart’s contents onto the upper shelf: clay and bronze statuettes, a colour wheel, painting and sculpting supplies—in short, all manner of things having to do with the topic at hand. Of course, we decide to strike up a conversation. The woman, who is friendly, explains that she volunteers for the museum on Wednesdays, dealing with visitors of all ages, discussing the paintings and sculptures with them, and explaining various artistic techniques. She even draws with them, which is interesting, because in fact, she has no artistic training: before retiring, she worked as an office administrator.

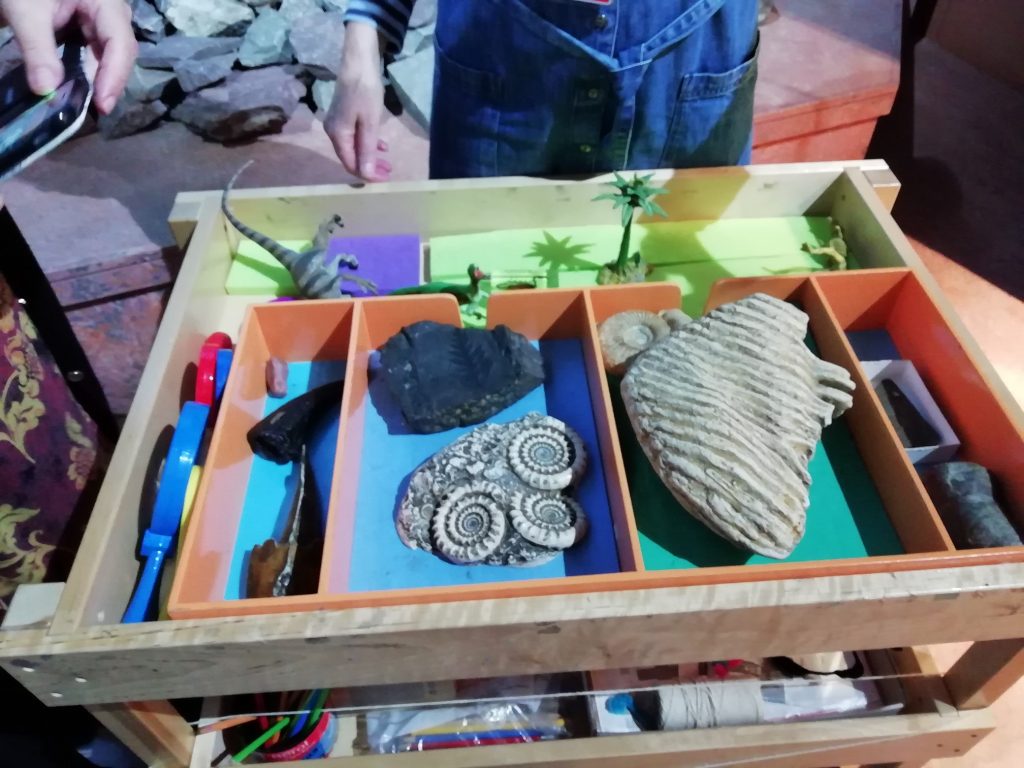

The left wing of the museum houses a natural history exhibition covering everything from the birth of the planet to modern environmental problems. Its main attraction is a moon rock that people come from far and wide to see. Here, too, there are active volunteers with tea trolleys. The range of offerings is impressive: a mammoth tooth you can touch, a miniature prehistoric scorpion, fossilised imprints, the tooth of a Tyrannosaurus Rex, and many other curiosities. “But what is this good for?” we ask innocently. The enthusiastic response is immediate and convincing: visitors take away not only information, but also personal, tangible experiences that really bring the exhibition home, to the satisfaction and delight of adults and children alike.

The left wing of the museum houses a natural history exhibition covering everything from the birth of the planet to modern environmental problems. Its main attraction is a moon rock that people come from far and wide to see. Here, too, there are active volunteers with tea trolleys. The range of offerings is impressive: a mammoth tooth you can touch, a miniature prehistoric scorpion, fossilised imprints, the tooth of a Tyrannosaurus Rex, and many other curiosities. “But what is this good for?” we ask innocently. The enthusiastic response is immediate and convincing: visitors take away not only information, but also personal, tangible experiences that really bring the exhibition home, to the satisfaction and delight of adults and children alike.

The National Museum coordinates an impressive volunteer programme, whose applicants all receive thorough training. Volunteers can each work in whatever field suits their interests, with no compartmentalising expectations of education or advanced training. In fact, there is even a volunteer with a mild disability who carries out her prescribed duties just like everyone else. The volunteers all inspire each other, support each other, and teach each other. Though the demo items on the themed tea trolleys are assembled by the regular museum staff, each volunteer uses only the items he or she chooses personally, things he or she feels comfortable talking to visitors about. The volunteers then submit suggestions for new materials based on visitor feedback, which the curators generally accept, a fact that supports their claim that volunteers are viewed as partners. What are volunteers good for? Most of them are freshly retired local people, primarily women, who use the activity as a means to learning and, therefore, to enhancing their own mental well-being. The volunteer team are active and maintain close contact with one another.

In the part of the exhibition dealing with the lives of the dinosaurs, we again make use of our explorer sets to bring the ancient skeletons to life. Dinosaurs roar, fly, scamper, and swim all about us, but otherwise cause no serious alarm. Though the digital world the device creates astounds us, it is not without a measure of danger. As our attention is drawn to the digital spectacle, we are not always aware of where we are putting our feet and repeatedly trip over the uneven ground.

To conclude the day’s activities, we visit Cardiff Castle, whose keep offers a spectacular view of the city and Bute Park. The audio guide we were given with admission proved extremely helpful in our exploration of the castle, its texts being simple, comprehensible, informative, varied, and layered with personal accounts and stories. Constructed in the Middle Ages over the foundations of a Roman fortress, then renovated during the 19th century in romantic Gothic style, the castle and grounds were gifted to the city by their last owner, John Crichton-Stuart, 5th Marquis of Bute, in 1947. According to the app that kept count for us, the visit added a total of 5,000 steps to our day’s trek.…

Kata Bodnar & Erika Koltay