It is a special experience for us when, at the end of the day, we arrive at the conclusion that, for the staff of the National Museum Cardiff and St Fagans National Museum of History, truly, the visitor comes first. Young, energetic professionals guide us through impressive exhibitions, exciting in both content and appearance, along with workshop spaces and open-air demonstration areas. Indomitable, the staff are delighted to talk about their work, their plans, and, surprisingly enough, the things they hope to change, replace, or rethink in the future. They have no qualms in telling us about things they at first thought a great idea but later found did not meet their expectations. Technology changes, as do visitors expectations, for which reason even certain elements of their permanent exhibition require rejuvenation every few years. For them, it is not a problem. “We’re not afraid,” says Riannon Thomas, an employee of St Fagans. “We know we may need to change parts of the project we’ve already finished. We check everything thoroughly before it is installed or introduced, but sometimes based on use or visitor feedback it turns out that a thing doesn’t turn out the way we expected. But no problem; we have to take it into account and handle problems flexibly.”

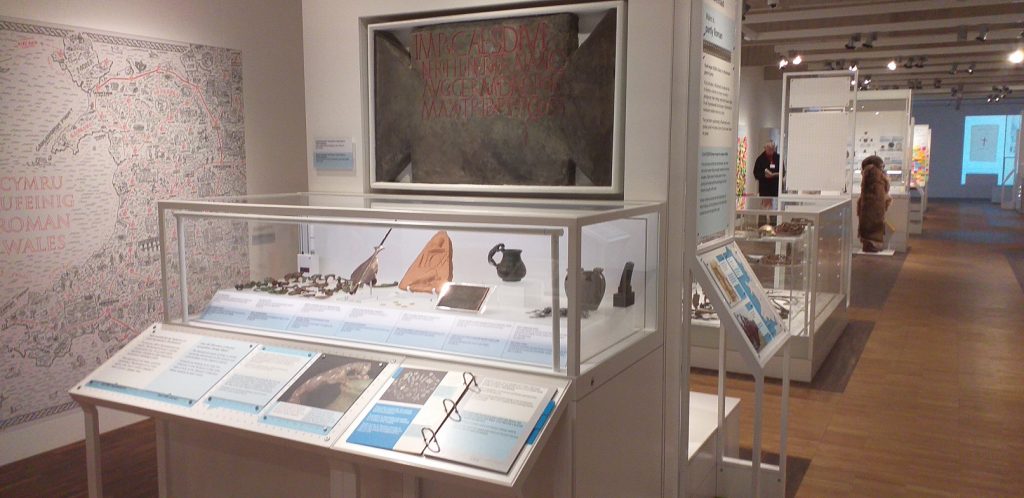

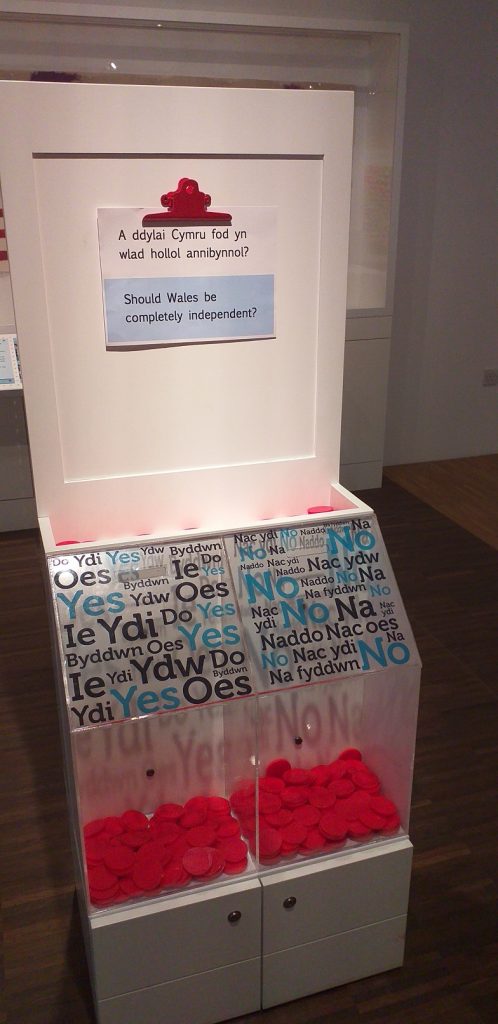

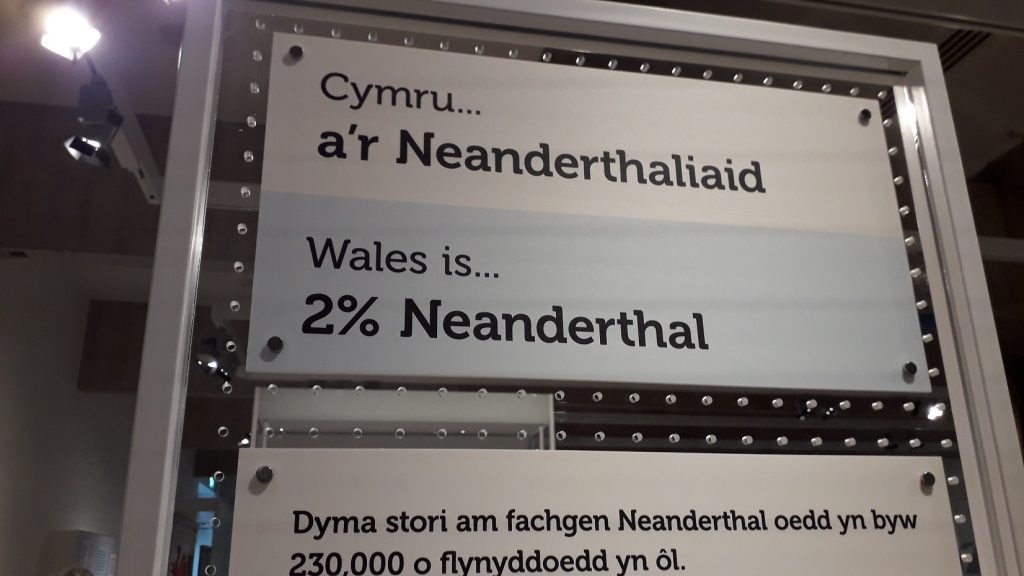

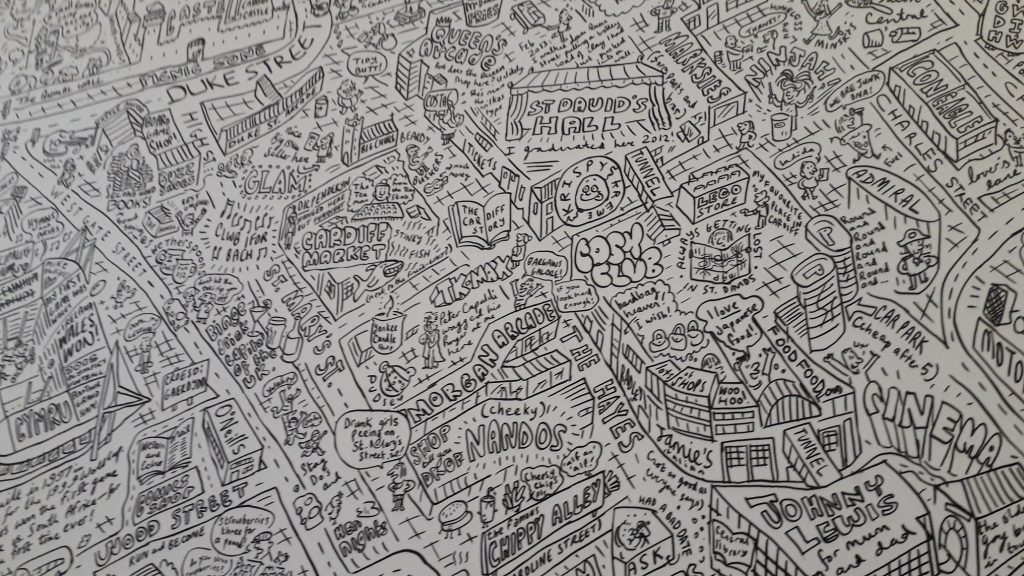

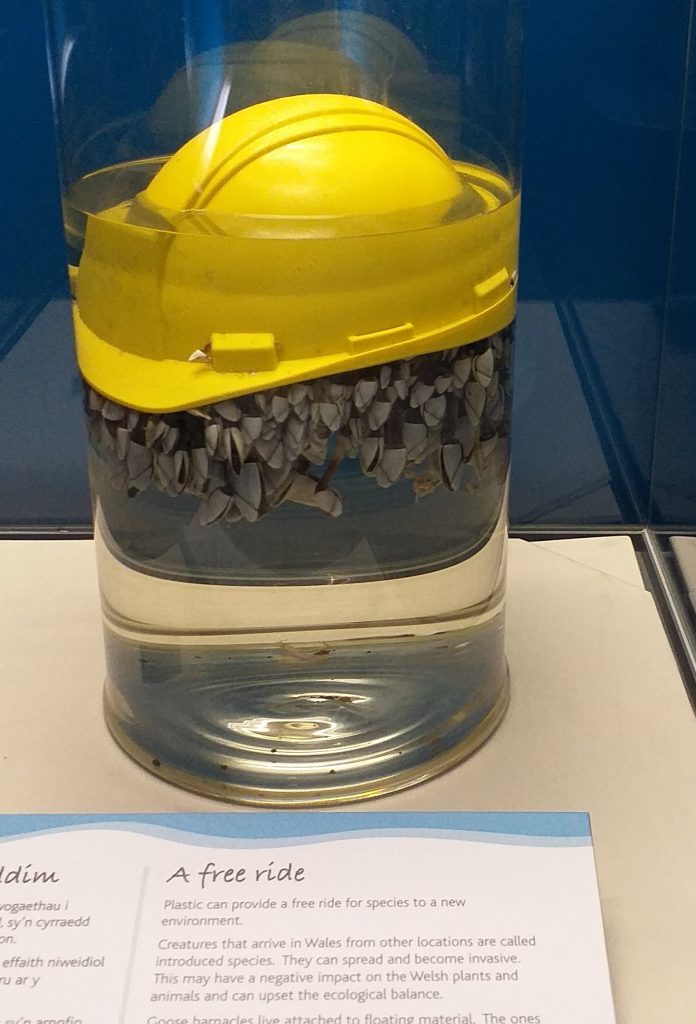

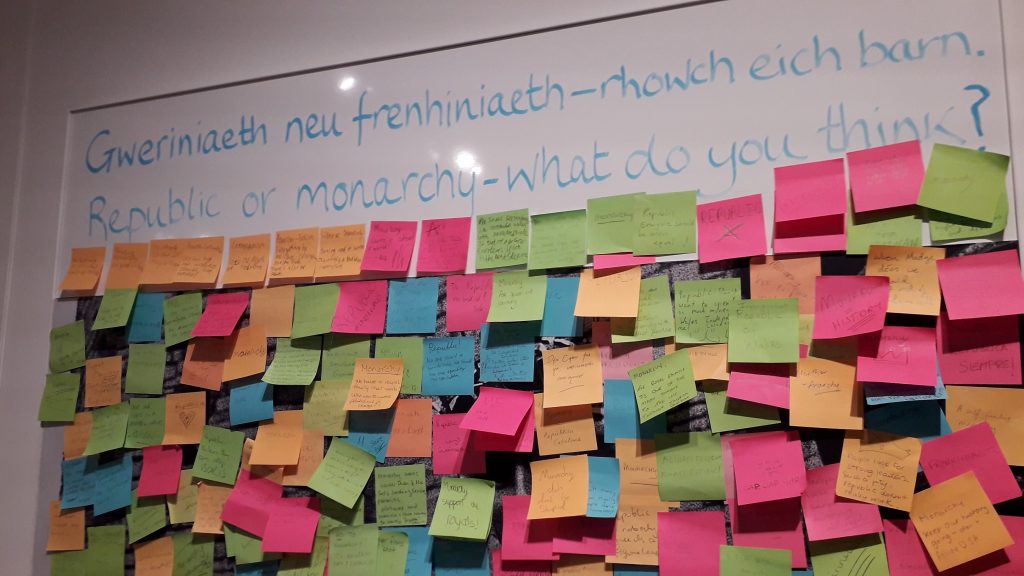

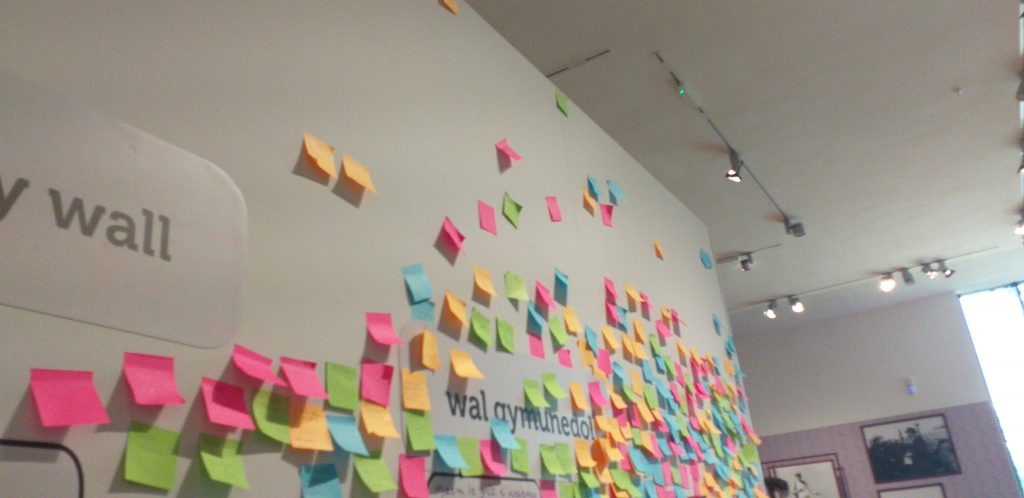

The natural history and fine art exhibitions of the National Museum of Cardiff are visited by more than 600 000 visitors a year. Recently, the archaeological history collection was transferred to St Fagans, a change that decisively impacted both institutions. Visitor feedback has helped curators choose for display objects and themes people truly want to see. Staff boldly ask questions and collect, analyse, and display the answers. It is a mystery, though, how those coloured response cards got all the way up there…

Though temporary exhibitions are frequently tied to admission fees, this does not seem to dishearten visitors. The museum’s workshop spaces are used by children, families, adults, university students, and civil groups alike. Parents are happy to visit the museum on a weekend simply to have their children do their homework in this environment. At the time of our visit, the enthusiastic participants of the institution’s “Drop in and Draw” program are gathering in the reception area—the group does free drawing in the early afternoon every Tuesday and Saturday (during the holidays in a group of 15-20, during the year in a group of 4-8). Twenty minutes or two hours: it makes no difference. All that matters is the joy of creation. University students often “hop over” from next door to join in. The majority of the regular group, however, are pensioners. One successful and greatly valued project from the previous year was carried out with a group of people who had “experienced homelessness”. The event shaped the thinking of museum staff in several ways. For one thing, it is clear that if the aim is to draw people in from the streets, then that must include the homeless, many of whom spend their days right there in the city centre. For another, as narrators, those who have no regular access to works of art can sometime express the very deepest thoughts about them. The encounter inspired all who participated in it. One member, for example, found work through the project. The real challenge, however, is to engage young adults, though this applies more to programme offerings than to exhibitions or museum education. Not even the Silent Disco or full fun programmes are guaranteed to draw them in, though it is interesting to note that as young parents they seem happy to return and spend time here. Certainly we’ll be back for another VR tour—in the company of Monet, some water creatures, and a dinosaur or two.